Here’s a post with no images at all. It’s a bit symbolic of my creative output since I last blogged.

Drawing aloud

The last couple of times we’ve been in residence at the Industrial Museum, it’s been when the machines have been running. In the first case, Greg was using the working loom to make a piece of cloth for a commission, so it was chonking away all day long, as I sat with my charcoal and ink.

The last couple of times we’ve been in residence at the Industrial Museum, it’s been when the machines have been running. In the first case, Greg was using the working loom to make a piece of cloth for a commission, so it was chonking away all day long, as I sat with my charcoal and ink.

I was attempting to draw more freely and instinctively; for some time I’ve been feeling that I was getting tight and anxious – tied up in the ‘tyranny of facility’ trying to get things right. So I’d come that day with sheets of paper which I’d prepared with a variety of ink washes. The idea was to look at the mass of machinery, choose a wash I thought worked with what I could see, and start drawing as freely as possible, maybe starting with a single motif and then, well, just busking it.

And Greg’s machine got into it all somehow, the sound of it.

YP Magazine, Jan 4 2014. Last chance to see…

YP Magazine

Jan 4 2014

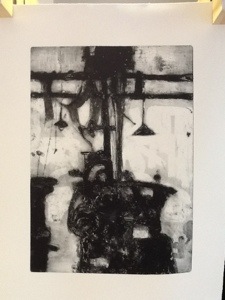

Carborundum – nice and black: June Russell

At the end of my second day of drawing in the weaving gallery, I finally found the courage to take on one of the looms in all its complexity. It was a long job, but I was very pleased with the result.

At the end of my second day of drawing in the weaving gallery, I finally found the courage to take on one of the looms in all its complexity. It was a long job, but I was very pleased with the result.

Since then, I’ve been turning over in my mind ways of doing justice to my drawing in print terms. It’s loose and atmospheric, with a lovely sense of movement, and I wanted to keep it that way; not to put it through a process that would tighten it up in any way.

A visit to Printfest in Ulverston last weekend gave me the answer. Among the 40 brilliant printmakers there, I particularly enjoyed the work of Ross Loveday who uses carborundum grit to develop large abstract landscapes. I used carborundum quite a bit when studying for my MA, but not since. I thought the possibilities for loose gestural marks might be just what I needed, so I dug out my old jar and had a go.

And this is the result. It’s one of only 2 prints from the plate, because the carborundum flaked off as inked, and the floor polish (used to create white areas) only ever survives one inking, but that’s fine. They are large prints, and carborundum is hard work, so that’ll do me. The image will stay fresh, as I wanted.

A pleb at the opera

I’d only been to the opera twice in my life before last night. The first was to see a local company perform in Bradford, at what is now Pictureville Cinema, but was then the Library Theatre. I love Pictureville, but the loss to the city of a community theatre with a raked stage and an orchestra pit is still a loss.

Anyway….I had a friend singing in that performance, so I went along. I’m afraid I didn’t much enjoy it; I can’t even remember what it was; something by Bizet, perhaps, I can’t be sure. I thought it was silly and dull. So that was it for 20 years.

My next experience, Opera North’s 2007 production of Dido & Aneas, was much more positive. I went to this, and dragged my partner along with me, because I have a thing about early music, especially Purcell. I absolutely adored it. But I was aware that this was a very different beast from ‘normal’ opera; it was short, and in English, with tunes.

‘Normal’ opera remained, to my mind, difficult, overblown and unrealistic, lacking in real plots or proper melodies, expensive and elitist. Most of all it felt as if it were not for the likes of us, the uninitiated.

I do love live performance though, and I hate to write anything off, so the invitation from Leeds Culture Vulture website and Opera North to see Verdi’s Otello in return for blogging about it seemed a great opportunity to have another go at working out what all the fuss was about.

I was prepared to enjoy myself if I possibly could, and the warm welcome from ON staff prepared me still further. My fellow bloggers were all as least as uninitiated as I, many of them complete opera virgins. We found a solidarity in our apprehension and, indeed, in our willingness to roll with this. A glass or two of wine and we were ready for anything.

I’d never been to the Grand Theatre before, so that was a treat to begin with, particularly as my first view of it was from the stage into the ornate auditorium – we stood in the performers’ shoes, wondering at what it would mean to sing out into such a space. There we met the lovely David Kempsey, who sings the not-so-lovely Iago, and discussed the technical and creative challenges faced, and embraced by an opera company. Speaking of opera as musical theatre, he was at pains to emphasise its accessibility. His own down-to-earth friendliness and charm probably served the cause in this as well as his words. A quick tour of the impressive staging for Otello, and it was time to take our seats, by now suitably primed, for the performance.

And the performance was grand. It started with a bang and ended in tears. Great stuff!

I was relieved to find that it wasn’t difficult to understand.The surtitles were incredibly helpful. I’d heard that their use has been a controversial issue since their introduction and that they are still deplored by some purists – I found an elderly but interesting article on the topic: why we have to learn to love surtitles . I try to imagine my experience without them – and without previous knowledge of the plot. I would have been lost. And, hey, scanning them whilst attending to the performance was much easier than tweeting through BBC Question Time.

It helped that I did know the plot, of course. I know it very well, in fact, since I used to teach Shakespeare to teenagers. It struck me that my students would have found this straightforward story, stripped of nuance but turbocharged with raw emotion, much easier to access than the text – initially, at least. I could have used this to inform their studies, had I known it then.

It was not as unrealistic as I’d feared. I did find that the casting which – and I can totally understand this – rests more on singing ability than looks or age, required a bit of suspension of disbelief. We have become far too used to physical uniformity in public performers. In comparison to the usual ‘standard’, these were a bit of a motley crew. However much I might applaud such diversity from an ideological standpoint, so rarely is it seen in public reality, that it took a bit of getting used to; about twenty minutes, I’d reckon.

There weren’t any tunes. I started off waiting for one to emerge and then gave up, deciding that my expectation was getting in the way of what else was on offer. Which was music that could go anywhere. I’m still not entirely confident about this, but by the end of the performance I was at least ready to accept it as a workable option. Because it did work on that indefinable level that we come to all creative activity hoping to find.

Listening to Othello and Desdemona’s duet, I understood, as I never had from readings of the play, how such an apparently ill-matched couple could possibly fall in love. From then on I was content to enjoy. And the final scene was so charged that I found myself hoping something would intervene to avert the tragedy. Daft I know, but it drew me in.

The liveness of the whole thing was a delight. I’ve never seen anything quite so live – so many people working together, in the moment, to make something so nicely coordinated. I had to constantly remind myself that the singers weren’t mic’ed up but were making those sounds with just their bodies, that it wasn’t a sound system accompanying them but a real orchestra – of people.

Of course, it’s expensive. Our complimentary seats would have set us back £50 or £60. However, seats can be had from as little as £15. This is no longer ‘elite’ pricing, when you weigh up the cost of tickets for more plebeian events such as football matches or rock concerts, all of which have ballooned in recent years.

I don’t think the evening’s experience will turn me into an opera lover. But I had a good time, and I no longer fear that it’s compulsory to become an opera lover to enjoy attending the opera from time time, as part of my general cultural pleasures. A good result, I think.

Etching in colour at last

Here’s how I make my colour etchings, these days. I used to try to try to apply colour ‘a la poupee’ – that’s rubbing colours on to the plate roughly where I wanted them to appear and putting the inked plate through the press just once. I found this very unsatisfactory. Not only is accuracy virtually impossible, but the resulting colour was pale and unsatisfactory.

Nowadays I ink the same plate 2, 3 or even 4 times, each time with a different colour. I still get a varied edition, but it’s easier to be accurate, and the resulting built-up colour has the depth and richness I’d been hankering after.

Here’s one I made earlier this week: River Valley II. It’s an open bite etch, on zinc, with a bit of added aquatint.

I start by inking it up with Prussian Blue and Alizarin Crimson in broad bands. I’ve made a template to position it on the press, using a piece of newsprint the same size as the paper it’ll be printed on, marked up with the size of the plate, in the centre.

I position the inked plate carefully on the template, and place the damp printing paper on top. I take it through the press almost but not quite all the way, so that the last inch of the paper is still caught between the rollers.

I remove the plate, clean off the blue and crimson ink and ink up again, this time with Sap Green, all over the plate this time, but wiped clean more in some areas than others.

I place the plate back on the press bed, exactly in the same position as before on the template, drop the printing paper down over it, and pull it through the press again

keeping my fingers crossed that:

the position IS exactly the same as before

I’ve wiped the plate clean in the right places, so that the colours beneath show through where I intend them to do.

Seven time out of 8 so far it’s come out right!

And here’s the finished print:

Be careful what you wish for

A brief Twitter conversation with Dan Thompson, of Empty Shops Network , about how fundamentally organisations change once they move from campaigning group to managers of a building made me reflect on my experience of working with The Art House between 1999 and 2009 during which time it underwent just that change.

The Art House was formed in 1994 by a group of artists, some with and some without disabilities, with the dream of a place where they could make art side by side. Since such a thing was unlikely to be achieved in short order, the group set to campaigning for accessible studio and exhibition spaces and opportunities more generally. The organisation grew, gained funding, took on staff, and met with considerable success. Always central to its campaigning was the aim of designing and constructing one purpose-built, totally accessible workspace that would act as a paradigm for what could be done and an incentive for others to emulate.

The Art House spent 14 years waiting for such a building, working towards it, fundraising and agitating and designing and constructing it . At last, in 2008 the completed building was unveiled. It was all we’d ever wanted. It was wonderful. Its opening was hailed as a watershed moment. It certainly was.

The Art House always had a national remit – how could it not? It was difficult to maintain this from Yorkshire (Curious that it’s never a problem to run a national organisation from London – that’s another topic altogether), but we worked hard at it, from our temporary bases in cheap office space. Projects were mobile and innovative. There were campaigns to make galleries and studios more accessible, installation projects that involved artists located throughout the UK and connected by the postal system, couriers or the internet. Exhibitions that toured widely, international collaborations, partnerships with disability organisations and residency programmes at national galleries.

Almost as soon as The Art House building opened, much less of its work was undertaken outside its immediate locality. ‘Come here’, we started saying, rather than ‘we’ll come over to you’. There were perfectly good reasons for this. We’d always struggled to find accessible spaces – now we had our own, so why continue so to struggle? And we needed things to be happening here, in our building; we needed to connect with the local community…

In response, the perception of the organisation by its members changed. We’d always had a higher proportion of members in Yorkshire, but while we were shifting from one temporary office to another, keeping on the back foot, looking outwards and holding our events at scattered venues, we presented as mobile and flexible. Once cemented into the new HQ, the proportion of members outside the locality fell rapidly as we came to be perceived much more narrowly, as an organisation for Yorkshire, for Wakefield, even. Despite our protestations, we heard artists saying: ‘you aren’t for us; we don’t live near enough.’

Activity started to focus inward for purely practical reasons, too. Now that we had the building, we had to feed it. Bricks and mortar need looking after. You don’t realise while you are renting a space from someone else, just how much work goes in to keeping it ticking over: maintenance, health and safety, insurance, cleaning, repairs, replacing the toilet paper! And we’d had capital funding to build the space, but had no funding to run it, so we desperately needed to sell room hire and to market community classes to keep revenue trickling in. There was an odd distortion of visual focus – the place had simultaneously to be kept looking ‘nice’ for business visitors and to be welcoming as a relaxed artists’ workspace. It all started looking and feeling a bit corporate.

So The Art House became – necessarily – a very different beast now that it has settled down and no longer roams free. Campaigning for accessible work and exhibition space still went on, still does, but it is now more often at policy level. The nationwide, artist-led grass-roots practical activity, which predated the burgeoning pop-up movement, but could and should now be part of it, is no longer a major focus of activity.

And, let me be clear, this is not criticism; it is simple description. The Art House is still doing great things, but owning and maintaining premises has fundamentally changed the way that happens, in ways that we never foresaw and that, perhaps, those of us who had fought hardest for it could cope with least well. I’d been an artist member from the beginning, and was employed as Projects Manager as we moved in. Over a decade of involvement in planning the move should have prepared me for the impact it might have upon the organisation, but it did not, and colleagues tell me they feel the same. It’s just a different job, altogether. Which means there’s work for a new organisation to be doing out there, somewhere.

Back to work at Redcar: Blast furnace in action

After a two year hiatus following the mothballing of the plant in 2010, steel is once again being made at Redcar. Sahaviriya Steel Industries, the Thai owners of the former Corus Plant reignited the blast furnace – the largest in Europe – on 15 April 2012

A month later, on a scorching hot day in May, I sat with a friend and sketched the furnace. Despite the heat we spent several hours working, fascinated by the huge structures, intermittently hidden by clouds of steam. Just before we left we were rewarded by the thrilling, unforgettable sight of a stream of red hot metal.

It’s a drypoint etching, using silvered card as a plate – a very fragile plate – which meant I only got 4 prints from it, all slightly different as I experimented with tissue and fingerprints to make the banner of steam across the image. The fourth print (not shown) is part of Printmakingonline touring exhibition and should shortly be at Eleven Gallery in Hull.

Unravel

Shine

Thanks to Louise Atkinson (Loubie Lou) I’ve been given a lovely big room at Shine in Harehills to hang much of my current framed work and the chance, fingers crossed, to sell some of it. In all honesty, I’m just pleased to see it all looking good, in one space, whatever the financial outcome. It’s like a little retrospective; some of the pieces date from 1996, when I first started making prints, while the most recent were creted just weeks ago at Bradford College